Is Bitcoin Fairly Distributed?

How would you bootstrap a new money?

You may have read the headlines about bitcoin's present distribution being concentrated among just a few whales. But snapshot analyses miss important facts about bitcoin's history and founding and the trajectory of its distribution. Both are relevant for assessing bitcoin's fairness and its suitability as a monetary network for all.

Imagine that you wanted to create a new money. You might mint a batch of units – magical beans, as it were – and award them all to yourself. Those beans would be about as useful as an invented language known only to you. Somehow those beans need to get into other hands.

So you might instead give them away. But distribution isn't enough. You also need to get people to value your beans as money. And it's hard to get people to value something that they've only ever freely received.

Perhaps you could sell them. But why should anyone want to treat as money these magical beans you sold or dispensed to your inner circle? And why should anyone trust you not to mint more beans and dilute the value of the ones you just sold? It makes sense to many that a startup business should have and benefit insiders: the reward for taking the risks inherent in starting a productive enterprise is selling shares. But, for very good reason, we don't treat shares as money. Money is supposed to be more neutral – more like public market infrastructure than shares in a private firm. So it would be fair to ask: who died and made you king of the money? Overall, why should anyone treat as money those beans that you both created and continued to influence?

It's a real pickle. How can we bootstrap a new money? Here is how Satoshi Nakamoto, bitcoin's pseudonymous creator, approached the problem.

Bitcoin's creator didn't freely mint money for himself or other insiders. There is exactly one way to mint new bitcoin: to complete proofs of work – that is, to burn electricity and processor cycles in the discovery of new blocks and to claim the accompanying reward of newly minted bitcoin. No exceptions. So Satoshi had to pay for his bitcoin, just like anyone else. He did not make magic beans out of thin air and hawk them at the local market. He bought them from nature, just like anyone else, and the price was energy. Mining has also been open to all since the network launched. So although bitcoin has early adopters, it has no insiders.

Not all cryptocurrencies follow this model. Some, in stark contrast to bitcoin, involve early rewards or pre-mines for their creators. Here, insiders acquire their units under different rules than others. Under a so-called "pre-mine", creators do not purchase their coins from nature in a free and open competition. Instead, they mint their units for free and sell some to others.

Markets have recognized bitcoin as king for thirteen years. Participants know that it is more fair than many alternatives and accordingly favor bitcoin in their behavior. Bitcoin's fair launch has, I suspect, played an important though subtle role in resolving the bootstrapping problem. Bitcoin has credibility because it came to be in a credibly neutral way.

Thus bitcoin's founding. And then, Satoshi – like Keyser Söze – walked away.

A creator's ongoing influence or control poses a risk. Think about it: would you accept some magic internet beans as money, if you knew full well that their creator could later alter them, dilute their supply, or push for technical modifications? You might if you trusted the creator or simply had to accept that creator's edicts as a matter of law. But this is not a viable path for a private money. Gadgets like bitcoin aim primarily to be neutral money without trusted authorities. For any would-be monetary engineer, this is a real bind. You want to make something useful whose usefulness doesn't rely on you. Failure on this front risks creating a cult of personality, or a legacy monetary institution that relies on trusted authorities.

Satoshi did the one thing he could to resolve it: he left. Without pomp or ceremony, he removed his name from the bitcoin website, handed over its keys to the community of developers, and quietly exited the spotlight. No one can say that Satoshi exerts undue influence over bitcoin development, or monetary policy, or culture, because Satoshi (under that name, at least) exerts no influence over those things.

In this way, bitcoin became leaderless and resilient. Its central bankers can't fiddle with its supply. Its CEO cannot, in a drunken haze, accidentally Tweet out something foolish, tanking market confidence. Bitcoin, Inc. cannot go bankrupt or have its assets frozen. There is no bitcoin Federal Reserve, no bitcoin CEO, no Bitcoin, Inc.

This description of bitcoin's founding may sound lofty and idealistic. But it has consequences in the real world too.

Bitcoin has been, for the entirety of its existence, the most valued, most studied, most used, and most widely-known cryptocurrency. This is no accident. After all, there are plenty of alternatives – over 13,000. And many of those alternatives have been around for over a decade; their existence is no mystery, and market participants can easily access them. I suspect that bitcoin's top ranking among cryptocurrencies reveals a preference for a leaderless cryptocurrency with a fair initial mechanism of distribution.

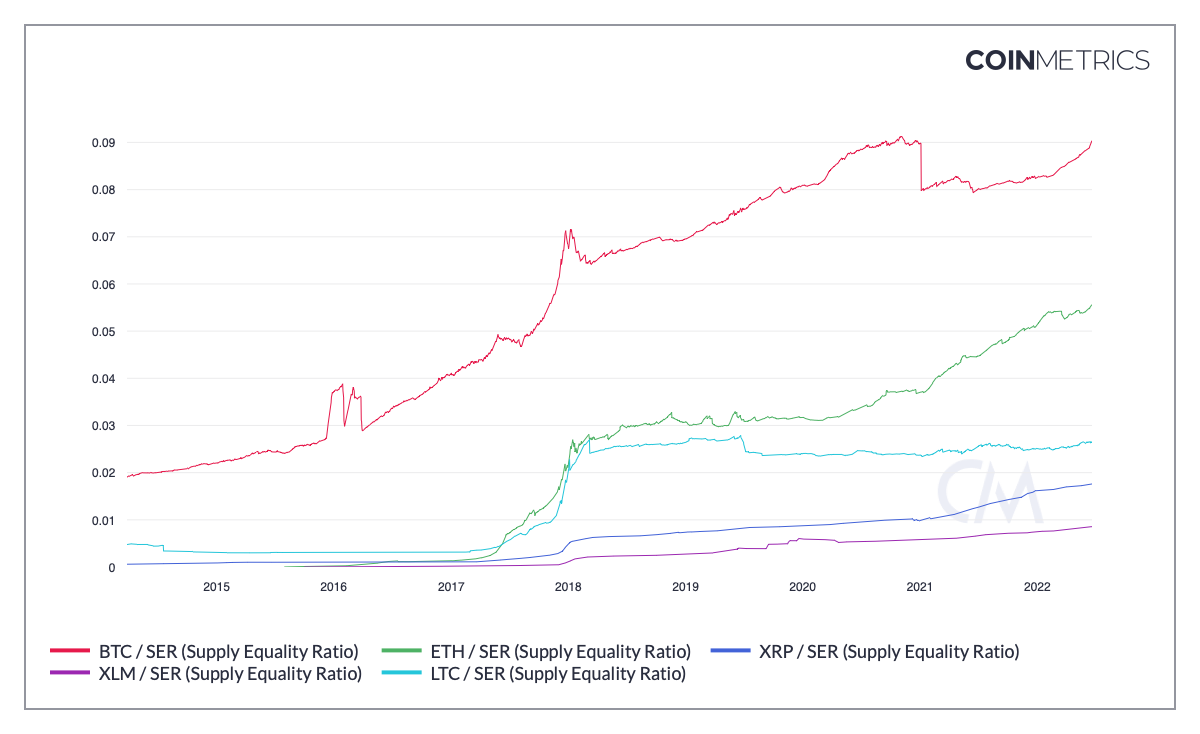

Bitcoin also enjoys a unique and healthy coin distribution. For the entirety of its existence, bitcoin's ownership has been less concentrated than its competitors' and it trends ever more in that direction. Following a report from CoinMetrics, I'll cite two measures in support of these hypotheses. First, we have Supply Equality Ratio (SER) – the ratio of "supply held by addresses with less than one ten-millionth of the current supply of native units to the supply held by the top one percent of addresses." A comparison of bitcoin's SER to a few competitors is instructive:

As CoinMetrics explains:

A high SER signifies high distribution of supply. As hypothesized, bitcoin has the highest SER out of the assets evaluated, followed by Ether and Litecoin. This is remarkable, since bitcoin is also the primary cryptoasset being custodied by large financial institutions; a trend that increases SER's denominator and puts overall downward pressure on the ratio. The sustained increase in bitcoin's SER shows that, in spite of large institutions entering the space, bitcoin is still very much a grassroots movement.

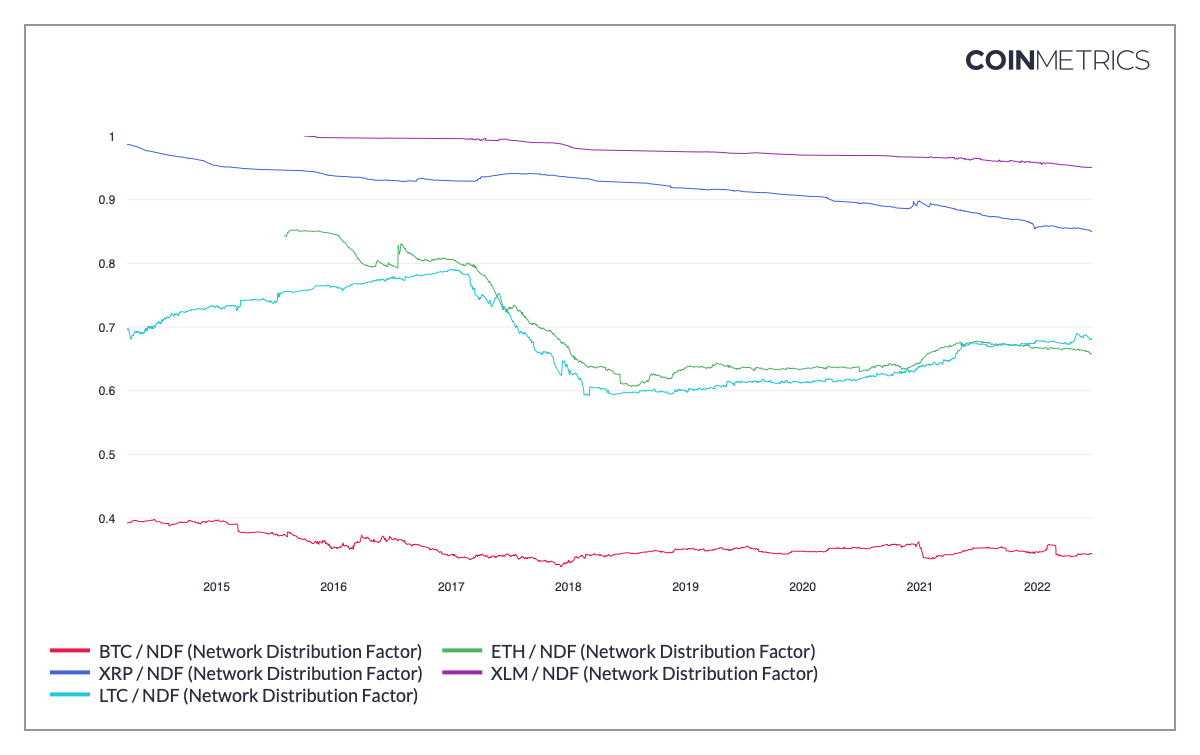

Another metric is Network Distribution Factor (NDF), which is the "ratio of supply held by addresses with at least one ten-thousandth of the current supply of native units to the current supply." Here, again, is how bitcoin fares against a few competitors:

Lower is better. Bitcoin shines again. As CoinMetrics explains: "A low NDF signifies better distribution as there are fewer entities at the top 0.01%. Conversely, a NDF close to 1 signifies a very low cryptoasset distribution."

More and more people own bitcoin. A network of one – Satoshi – blossomed into an ecosystem involving millions. Bitcoin is young, and it remains a niche money. Its distribution is not nearly as wide as the dollar's, say, or many other fiat currencies. But thanks to its fair founding, it seems to be trending in one direction – global adoption.

.svg)

.png)

%20copy%205.png)