Now Is the Time to Think About Value

The transformations we are seeing in the world around us—in systems of government, geopolitical alignments, economic institutions, and received wisdom—make now a particularly appropriate time to be asking the question, “What is value?”

It turns out that answering this question is not straightforward. We all have a sense that we know what value means, but we are often surprised by the ways it manifests in everyday life. For example, why do people sometimes seem to act against their own self-interest? Who determines whether something is valuable, and how? What is the nature of the relationship between growth and debt? Ownership and wealth? And how does all of this relate to qualities of character, like trust, and integrity?

These are important questions, relevant to most disciplines—economics, finance, government, computer science, the arts, the natural sciences, and many more. Ultimately, truth and value are inextricably connected. Anyone seriously in pursuit of truth is also in pursuit of value.

Every era of major transformation is a time of both crisis and opportunity. How we respond to it determines the trajectory the transformation takes. Humanity can solve some of the most intractable problems—poverty, social inequality, opportunity dead zones, sterile institutions, climate crisis, information warfare—by working together.

To start, let’s look at the world we live in and the challenges we face.

The Situation

We're living in strange times. Political polarization is at generational highs in the US and in many countries around the world. Charismatic political leaders and parties exploit social divisions to heighten hatred and mutual suspicion within their populations, propelling themselves to electoral victories.

Since the end of 2019, a global pandemic has swept the globe, killing over a million people and infecting over 40 million as of this writing. The novel coronavirus (COVID-19, or SARS-CoV-2), which affects the lungs, kidney, heart, and brain, may produce a severe illness that often takes much longer to recover from than most flu viruses. Mortality rates for COVID-19 are still being estimated, but scientists at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine suggest it may be ten times deadlier than most strains of the flu. The disease offers no immunity from re-infection, which also means building herd immunity to the disease is impossible. It has resulted in harrowing, lifelong medical complications for many survivors.

The COVID-19 pandemic has pushed the US economy into a historically unprecedented state. Like a dissociating patient, its real economy and financial economy have split into two completely distinct realities. The US real economy (representing profits, growth, and job creation) contracted at a never-before-recorded rate of 32.9% in Q2 2020. Q2 2020 beat the previous quarterly record for fastest drop in US GDP growth—Q3 1893, which saw a crippling depression with -8.4% growth following a run on the banks. By contrast, the US financial economy—specifically, the equities market—has been skyrocketing to all-time-highs. (The trajectory of the credit market has been much more mixed.)

It is not the pattern of a split between the real and financial economy that is unprecedented. Stock prices rose in seven of the past twelve recessions going back to the Second World War, and the 2008 crisis was no exception. During an economic contraction, money often flees to a conservative position of fiat currency, bonds, and safe equities. In addition, government stimulus money given to corporations is rarely used to keep people employed; instead, temporary furloughs become permanent layoffs, which boost earnings results—raising stock values in turn. Moreover, the particular nature of the COVID-19 crisis has rapidly accelerated a shift to digitization of both consumer and enterprise services and business processes, boosting technology stocks to all-time highs. Indeed, almost all of the gains in the equities market came from the technology sector, whose top companies are seeing record earnings and their highest valuations in history.

What is unprecedented is the magnitude of the split between the contraction of the real economy and growth in the stock market. It reflects the historically high gap between the highest and lowest earners and the fundamentally different ways in which these groups deploy capital. Income inequality in the US is now at the same levels it was just before the Great Depression. Since 1989, the total US wealth controlled by the bottom 50% has been cut nearly in half (from 3.6% to 1.9%). Between 50% and 75% of Americans now live paycheck to paycheck, meaning they rely upon ongoing income from their own labor to make ends meet. About 30% of Americans have no savings at all, and 40% of US adults don’t have a spare $400 in cash, savings, or credit they can quickly pay off. The bottom 90% of Americans own most of their wealth in their homes and are burdened by over 75% of the country’s private debt.

In other words, despite the longest economic expansion in US history, record low unemployment (3.5% by the end of 2019), and wage increases (including minimum wage increases in more than 20 states), most Americans are leading lives characterized by deep economic insecurity. Wage increases at the bottom haven’t come anywhere close to the increases in income and wealth occurring at the top. When adjusted for inflation, average wages for most Americans have barely increased since 1974. This is despite the growing productivity of the American worker: net productivity has increased by over 100% since 1979. While the 1940 Fair Labor Standards Act limited the workweek to 40 hours (8 hours per day), many Americans across the economic spectrum work significantly more.

Some have argued that this comparison is unfair, because it excludes benefits received by workers and doesn’t take into account the great advances in product quality and prices that have improved quality of life for everyone. It is undoubtedly true that advances in connectivity and consumer technology have empowered and made life easier for ordinary people unlike anything before. Yet, such an analysis doesn’t take into account that the costs of housing, healthcare, and education--major expenses necessary to live lives of productive citizenship—have spiraled upward in recent decades, becoming less affordable than ever even for families with means. The median price of home sales has increased 39% since 1974, while healthcare costs have increased by $9,000 per person since 1970, and the cost of education has more than doubled since 1971.

In other words, employer benefits are paying for less now than in the 1970’s, even if they may be spending more. And while many in the poor and middle class may enjoy the benefits of smartphones, advanced computing, and near-ubiquitous web connectivity, this doesn’t resolve the economic precarity that keeps them living paycheck to paycheck in tenuous jobs that increasingly lack the benefits offered full-time employees.

By contrast with the bottom 90%, the total private national wealth owned by the top 10% of US households has risen by about 10% since 1989, to 69% of all US wealth in 2020. The top 1% of US households now own 15 times more wealth than the bottom 50% combined. They also own more than half of the national wealth invested in stocks and mutual funds, but only about 5% of private debt in the country. In other words, those at the top of the economic pyramid are virtually unexposed to contractions in the real economy, or to price increases in education, healthcare, and real estate. So long as they steward their asset portfolios well, they can mostly continue making money no matter what happens. It is no surprise that a 2019 Georgetown Study found that wealth, not ability, is the biggest predictor of future success in America.

This means there is a profound division between how the top 10%--and especially the top 1%--experience an economic contraction and how everyone else does. And an economic contraction during a pandemic is particularly harsh. Unemployment rates during the COVID-19 crisis have exceeded those during the 2008 Great Recession, reaching levels that last prevailed during the 1929 Great Depression. Nearly 50 million Americans have filed for unemployment at some point since March 2020. About 40% of households earning less than $40,000 per year were laid off or furloughed by early April. Although many of these people have found employment since their initial filing, these jobs are often temporary and precarious.

The vast majority of this group was likely part of the 50%-75% of Americans living paycheck to paycheck before the pandemic. This has resulted in a spike in food insecurity. Before the pandemic, about 10% of US households were food insecure, but the COVID-19 crisis more than doubled this number to 23% of US households. Among households with children, the rate rose to nearly one in three (29.5%). Enrollment in the expanded Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) grew by 17% from February to May, but it was not sufficient to meet the growing need.

Similarly, when COVID-19 struck, nearly half of all renter households in the US were already rental-cost burdened, meaning they paid over 30% of their income on rent. 25%, including over half of all renters below the poverty line, were paying over half of their income towards rent. Already facing rent insecurity, up to 40 million Americans are now at risk of eviction. Of those rent-insecure Americans, approximately 11 million are behind on rent as of September 2020, representing one out of six adult renters. That number does not include the approximately 10 million homeowners—10% of the homeowning population—who are behind on their mortgage payments.

Finally, in 2019, before the pandemic struck, 30 million Americans already had no health insurance. The number of uninsured had been increasing steadily since 2016 (reasons for this increase are still disputed). Because most Americans rely on their employer for insurance coverage, as of late August 2020 an additional 12 million had lost coverage when they lost their jobs as a result of COVID-19. Their options are grim: to continue their previous employer’s coverage under the COBRA plan, they must pay what they were previously paying each month while employed as well as paying their former employer’s contribution. This is often prohibitively expensive. Alternatively, they may qualify for a plan under the Affordable Care Act, but it may not be less than their COBRA payment. Finally, Medicaid may be an option, but only if they meet their state’s eligibility requirements. For example, collecting unemployment benefits could render some people ineligible for Medicaid, leaving Americans in a double bind: do I seek unemployment benefits or health insurance?

If it seems particularly harsh to lose healthcare coverage during a global pandemic, that is because it is. The number of Americans regularly facing the decision of whether to buy life-saving medications, like insulin, or groceries was already troubling pre-pandemic, but now has increased dramatically. And while COVID tests at certain locations are now free, they can still cost money at “non-public sites” like emergency rooms—and patients often aren’t told the difference. Independent nonprofit FAIR Health estimates that uninsured patients, or insured patients who receive care deemed out-of-network by their insurance company, can expect to pay anywhere from $42,486 to $74,310 if they are hospitalized with COVID-19. Those who are insured don’t fare much better; insurance just cuts their costs about in half ($21,936 to $38,755). Some patients do pay less than this, but many patients pay much more, especially if they have additional health complications. The fragmented, complex nature of the US healthcare system means that patients often can’t know what their treatment will cost until they receive a bill.

The numbers above paint a striking picture of two Americas, divided by class (which, as we will see in future posts, is also heavily overlapped by race), being asked to choose who will represent them politically during a time of economic precarity and upheaval. But while the coronavirus pandemic has undoubtedly exacerbated existing social and economic divisions within the US, it has also shed light on the instability underlying the US financial system. This has led to profound concerns that any steps taken to ease the devastation of the COVID crisis could hasten the collapse of the system itself.

Economic Solutions

The instruments typically employed by governments to manage economic crises—fiscal and monetary policy—are proving their limitations in real time. On the fiscal policy side, it is clear that federal government stimulus—via direct payments and loans made to state governments, businesses, and individuals—staved off the very worst of the potential human suffering for at least some of the 90%. It also significantly boosted both credit and equities markets, as well as consumer confidence. However, as shown above, it has been insufficient to remedy the nationwide humanitarian crisis, and the government will likely soon pass another stimulus package. Much like the decade following 2008, it is probable that the US government will continue to deficit spend at high levels, for a long period of time, to stimulate the economy.

On the monetary policy side, the Federal Reserve has deployed a tool honed during the 2008 crisis: quantitative easing. By employing unlimited quantitative easing (sometimes colloquially called “money printing”), the Fed has reinvigorated bank liquidity, propped up failing corporations, and promoted consumer spending. This may achieve some of the government’s economic objectives, but at the cost of the overall creditworthiness of the United States. This is because every bout of QE significantly increases the US’s Debt-to-GDP ratio, which signals to credit and capital markets how much money the United States is generating annually (GDP) to pay off its debts. Between Q4 2007 and Q4 2012, the US Debt-to-GDP ratio ballooned from 63% to 100% as a result of QE deployed to recover from the 2008 economic crisis. As of Q1 2020, the ratio stood at 107%. As of this writing (October 2020), the US Debt-to-GDP ratio is over 130%.

In the past century, 51 out of 52 countries with a 130% sovereign debt-to-GDP ratio have defaulted. (Japan is the only counterexample, but we shall see why in a moment.) Default is a situation where a country’s treasury can no longer service its debt. If the US defaults, the consequences would be catastrophic for not just the US, but the world. Hundreds of billions of dollars of foreign investment would likely be removed from the US immediately, crippling the economy. Many countries hold significant amounts of US treasury reserves, and would be unable to collect their value, losing assets that add up to significant percentages of their GDP. International confidence in the dollar would crumble, and the US would no longer be able to borrow on favorable terms (if at all). US assets might be seized around the world. US Treasury rates would spike, and since US mortgage and student loan rates are tied to treasury rates, most Americans would see interest rates on their private debt shoot upward. This would trigger a wave of private defaults even more significant than what we have already seen in the housing and student loan crises to date. A global depression would likely ensue.

Despite its astronomical debt, however, a default of the United States is impossible. Quite simply, all of the United States’ debt is denominated in dollars, its own sovereign fiat currency. That also means that the United States is the only country or entity in the world that can issue the currency used to repay its own debt. The Federal Reserve can immediately generate all the dollars needed to repay its debt by just creating the money on its digital ledger. This is why Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, French Minister of Finance during the 1960s, famously excoriated the “exorbitant privilege” of the dollar.

Japan is in a similar position to the US; all of its sovereign debt is denominated in its own currency, the yen. In addition, 50% of the debt is held by the Bank of Japan, the country’s central bank, and another 40% is held by Japanese investors. In essence, Japan primarily owes itself. Thus, by keeping interest rates very low, Japan can continue servicing its debt relatively easily. This has allowed Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio to balloon to over 250% with relatively few negative repercussions for the economy—at least in the near term.

The UK and China also have domestic debt denominated in their own currencies. A default of these countries is therefore also extremely unlikely.

However, default is not the only reason to avoid debt. The main problem with endlessly printing money to pay down debt is that, over time, it devalues the money itself. Conventional wisdom holds that this is because it hyperinflates the currency, but in fact, currency devaluation and hyperinflation are two different things. As investor and strategist Lyn Alden shows, currency devaluation has only been inflationary in the US when federal and private debt is very high as a percentage of GDP and Congress begins deficit spending that gets monetized by the Fed (rather than funded by private lenders). In other words, exactly what is happening now. The resulting devaluation of the currency also devalues everyone's debt, which, in turn, prompts lending and spending. Once this happens, however, only a modest increase in monetary velocity is needed to bring about high inflation, which further decreases purchasing power.

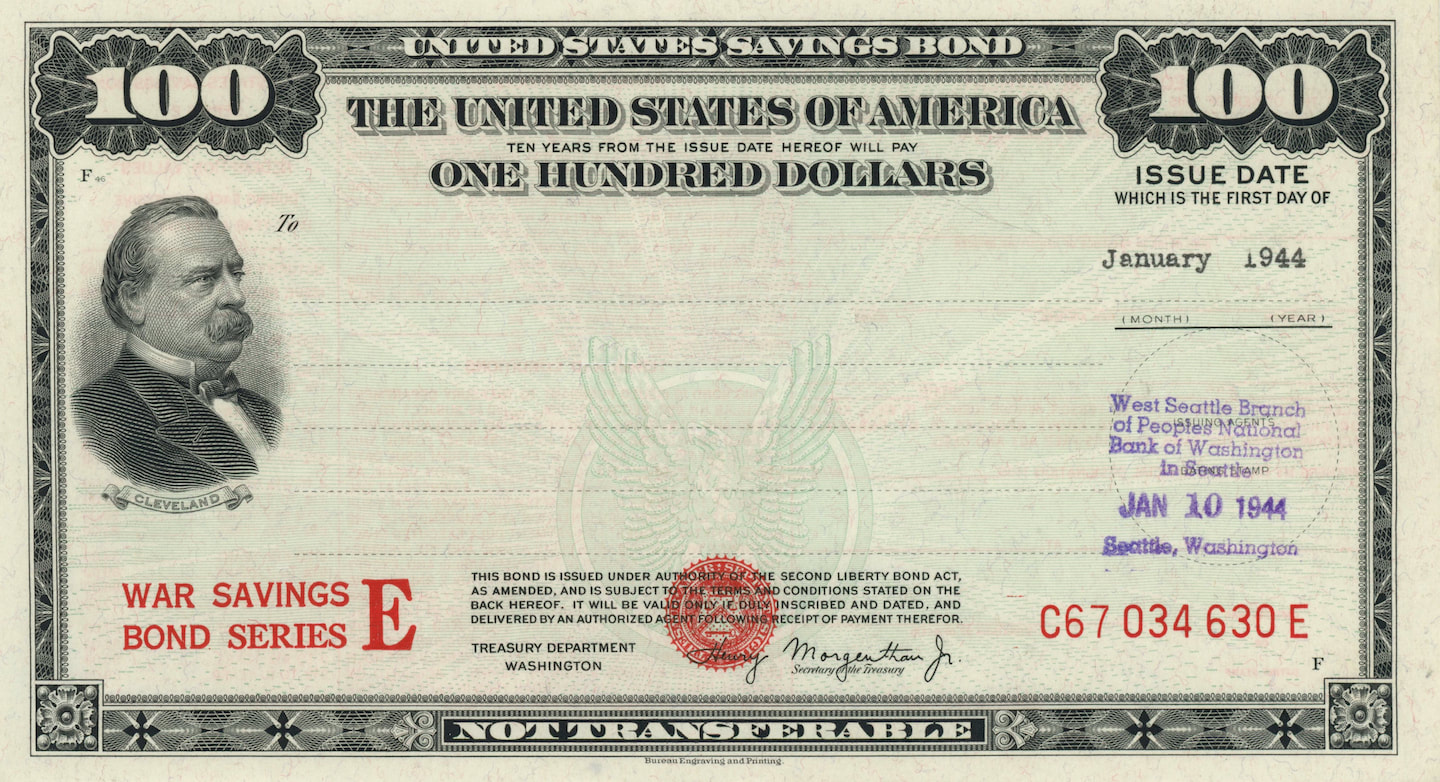

Alden demonstrates how the US dollar has been systematically devalued over the past century as part of debt “supercycles.” This means that savers and investors with a large amount of currency exposure have lost significant purchasing power, even if they've seen returns in nominal terms. In other words, simply “adjusting for inflation” isn’t enough to understand how much money people are really making over time; the value of the dollar has dropped to the extent that even people seeing returns on investment higher than the rate of inflation over the past several decades have had significant amounts of their wealth destroyed. The statistic cited earlier—that the average, inflation-adjusted wage of most Americans has barely budged since 1974—doesn’t take into account currency devaluation. As a result, we can infer that the average American is actually making less money than they were in 1974.

The only way to beat the dual forces of inflation and currency devaluation and actually grow one’s wealth over time is to invest in assets that appreciate in value so fast that they break out of the combined gravitational pull of inflation and currency devaluation. These tend to be equities, but even such rapidly-growing equities are rare. Nevertheless, the few equities that do grow reliably fast over a long enough period of time can generate net new wealth for entire societies, if enough capital is leveraged to them. And entrepreneurs who build new companies generating new value can create significant personal wealth for themselves, their employees, and for other shareholders via well-timed liquidity events.

Recently, Bitcoin has been showing similar patterns. As the world’s first truly decentralized, non-sovereign currency, Bitcoin unsettles central banks because it’s fixed—deflationary monetary policy is beyond their control. There will only ever be 21 million Bitcoin, each of which is subdivided into 100 million Satoshi. This digital scarcity ensures that it cannot simply be “printed” to pay down debts. In this way, it is more akin to gold than to most currencies, but it also has other features of currencies, like fungibility and portability, that make it useful as a medium of exchange. It is therefore a new kind of money. Bitcoin’s relative novelty in the marketplace has shown us a real-time process of price discovery reflecting a dawning comprehension of its value. This value, expressed in price, has skyrocketed along a parabolic trajectory since it was launched in 2009.

The US is not the only country where the value of currency has been systematically depreciated. Brazil, China, Japan, the UK, and the Eurozone are all major economies that have dangerous levels of debt and monetary policies that allow for the unlimited creation of money to pay down that debt. This is why the launch of Bitcoin as a global store of value is poised to offer a stable foundation during a time of what may be wild fluctuations in currency values. At the very least, it offers a vehicle for growing and protecting wealth in an era when central banks are growing their balance sheets to eye-watering levels.

The Next Step

The situation described above—political extremism and polarization, a pandemic, declining standards of living, rising wealth inequality, dangerous levels of national debt, and a bipartisan political system inherited from the mid-20th century—is what ordinary Americans face. To escape it, we need a better understanding of what we mean by stores of value, credit, and, of course, debt. We need to take a closer look at these categories because they help us describe the circulation of value in a society and give us insight into how engines of wealth generation may be preserved regardless of the fate of any particular store of value, indebted institution, or defaulting debtor. Only through exploring, understanding, and acting can we create the change that lifts us up and leads us forward into a future that is bright for American and global citizens alike.

.svg)

.png)

%20copy%205.png)